* Western Zhou Dynasty 1046-771 BC

* Eastern Zhou Dynasty 770-256 BC

* Spring and Autumn Period 770-476 BC

* Warring States Period 475-221 BC

Witch doctors

In the Shang dynasty - the dynasty before the Zhou - people's perception was that illness was caused by the dissatisfaction and wrath of diseased ancestors. In the Zhou dynasty this notion was transformed into the believe that demons are the cause of illness, which marked the beginning of what is called today "demonic medicine". The believe that demons are the source of illness can be found in the literature of the later Zhou, as well as the following Qin and Han dynasties with expressions defining illness such as “struck by evil”, “assaulted by demons”, “possessed by the hostile influence of demonic guests” and “possessed by the hostile”. In the Wushi'er Bingfang, or Recipes for Fifty-Two Ailments - the earliest Chinese medicine reference in China - twenty seven prescriptions are based on spells(3).

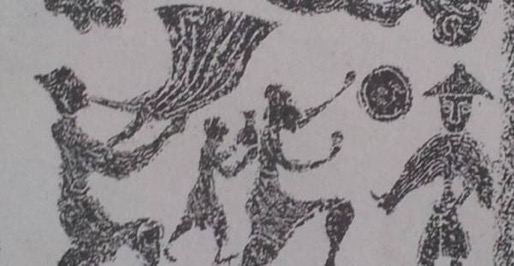

During that time medicine and magic were indistinguishable. They were practiced by shamans/witch doctors, known as wu (still to be found in North Asian tribes today).

The meaning of 巫 wu is "spirit medium”, “shaman”, “witch doctor". Wu 巫 was depicted in the lower half of the ancient character yi 毉 - "healer; doctor"(1). In fact shamans and doctors during those times were refereed to with the collective name “wu yi” -"shamans-doctors". It was later on during the Spring and Autumn period when shamans and doctors began to separate. Shamans were bind to cure the ill through evoking the power of ghosts and gods, while doctors began curing the ill through examination and medication(1).

Earliest Health Care System

The development of medicine during the Zhou dynasty was concentrated in the palace(8). According to the Rites of Zhou imperial court physicians in the Zhou dynasty were divided into four categories – dieticians (食医), physicians (疾医), surgeons(疡医), and veterinarians (兽医)(2). They all had to receive specialised training and were responsible for certain medical conditions - the medical doctor was responsible for the treatment of diseases, fractures or other traumas, the dietician was responsible for the nutrition regimen in the palace, the physician in charge of the treatment of animals was China's first authorised veterinarian, etc. Thus at that time medicine began to get classified. According to the Book of Rites there were now systematic medical organisations(8). A system for case studies and death reports also developed in the Zhou dynasty. Rites of Zhou says,” when they fall ill, people are treated by physicians of different medical branches. The result of treatment is recorded as experience. When one dies, the cause must be made clear"(2).

Prominent people in medicine. The emergence of Daoism.

A prominent doctor from the time of the Zhou dynasty is Bian Que (407-310 BC) . He became known during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States Period and lived about the same period as Confucius (around 552–479 BC). His real name is said to be Qin Yueren (秦越人) but his medical skills were so remarkable that he was considered a “divine doctor” therefore the people called him with the name of the legendary doctor Bian Que who lived at the time of the Yellow Emperor(1).

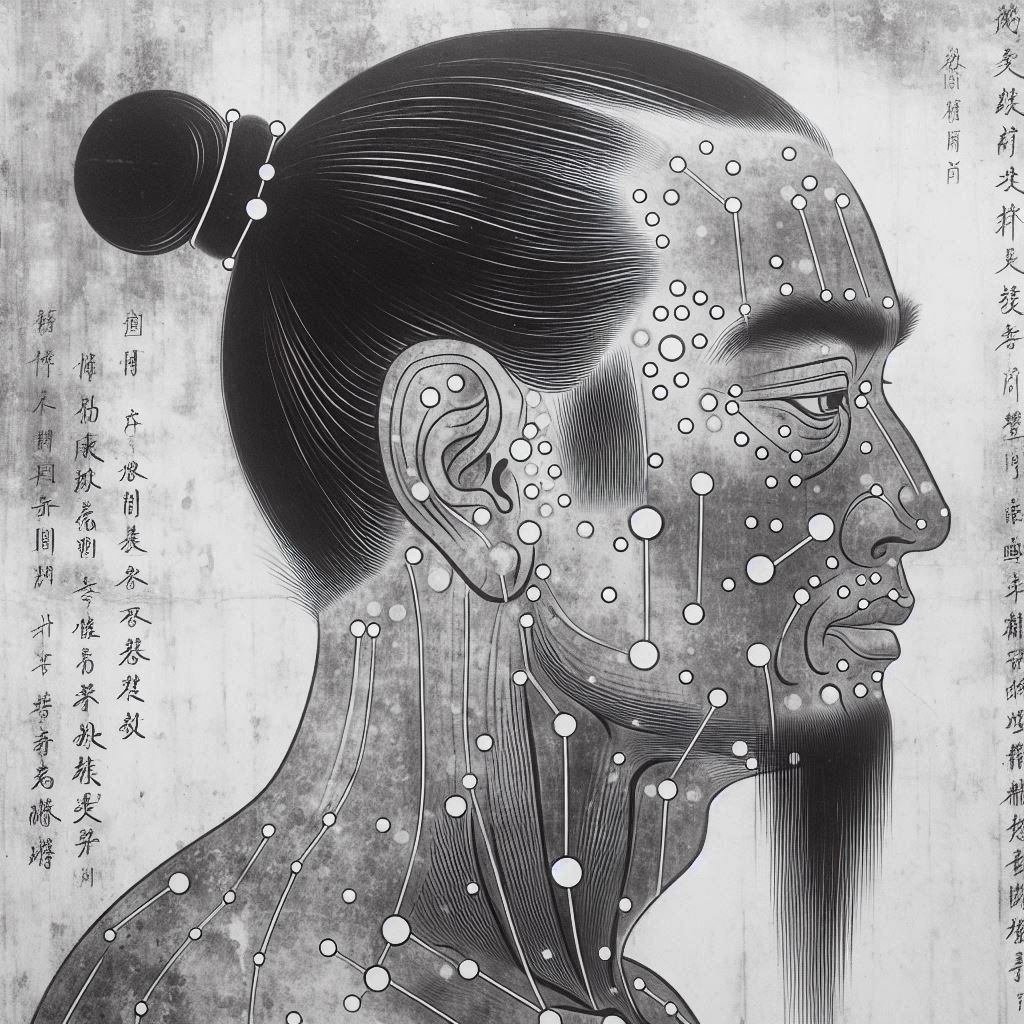

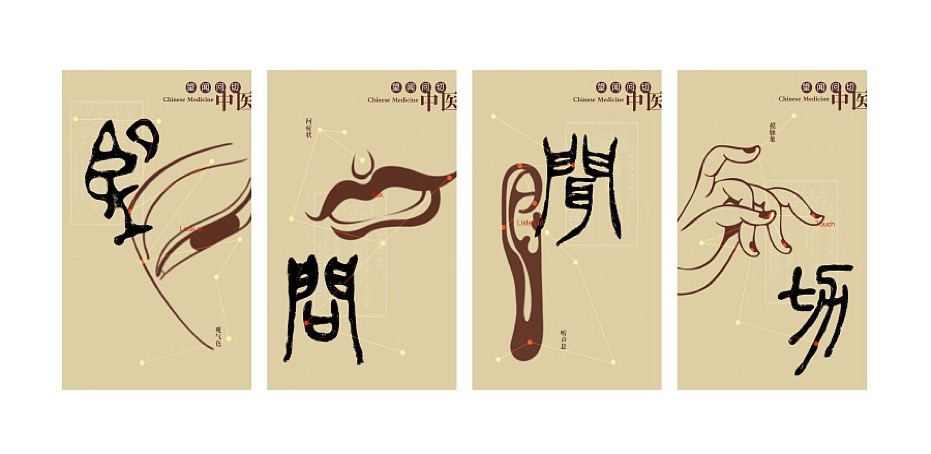

Bian Que is traditionally credited with the founding of the four methods of diagnosis in Chinese medicine, called the 'Four Diagnostic Methods'—looking, listening/smelling, asking, and pulse-taking. “Looking” is observing the patient's tongue, ears, nose, eyes, face, mouth, and throat; “listening” is auscultating the patient's tone, cough, or other body sounds, “asking” is inquiry into the patient's pathogenesis in detail, “Pulse-taking” is taking the patients pulse for diagnostic purposes. Today every Chinese medicine practitioner uses these four methods as mandatory part of making the diagnosis.

looking asking listening pulse taking

In the pre-Qin period prevention of illness was largely advocated. The word “prevention” is first seen in the “Xi Bu Ci” - to treat the illness with caution, in order to prevent devastation. “Yi Jing” put forward specific measures - as long as people do not flow everywhere, the disease will not spread and the numbers of the infected people will be reduced. Bian Que also attached great importance to the prevention of disease. He repeatedly persuaded early treatment with the idea of preventing the disease before it materialised. He believed that measures need to be taken in advance to eliminate the disease from its root, which will achieve more results with less effort(1). Today Chinese medicine is widely known as a preventative medicine which has the tools to capture and address illness before it has physically manifested.

During the Zhou dynasty theoreticians who tried to integrate man and his environment into a cosmic structure emerged(1). Zou Yan was a noted cosmologist who compiled lengthy treaties titled "Ends and Beginnings" and "The Great Sage". According to the Shiji Zou Yan described the outer world as a phenomenon that cannot be measured using the small scale of the human world therefore he established the method of “analogical inference” that would enable people to understand imperceptible spheres such as the universe(5). He was most importantly versed in the mysteries of Yin and Yang and the Five Powers of Virtues (wu de, later known as the Five Phases - wu xing 五行)(6). Zou Yan is commonly associated with Daoism and the School of Naturalists.

Another Daoist - believed to be the co-founder of Daoism - was Zhuang Zi(1). He believed that the universe was formed naturally, without design or purpose. Dao is Nature, the creator. It has no conscience, it does not judge. It supports all things - living as well as nonliving, without conditions. Zhuang Zi is quoted to say “Heaven and earth and I live together; myriads of things and I are but one”(7). Zhuang Zi is credited with writing—in part or in whole—a work known by his name, The Zhuangzi, which is one of the foundational texts of Daoism.

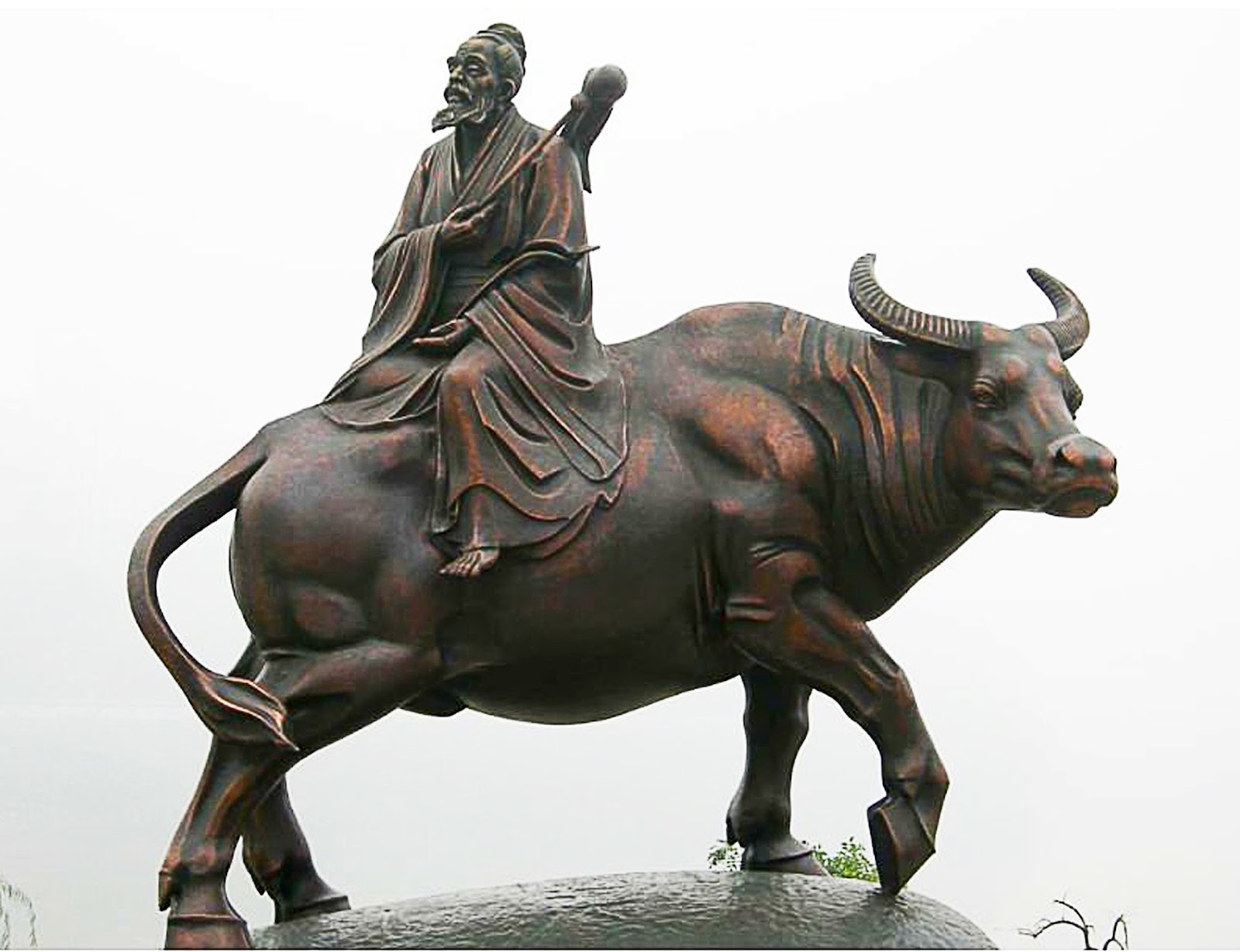

When we think about Daoism one prominent name comes to mind - Lao Zi (“Master Lao” or “Old Master”). He was born 590 BC and was a contemporary of Confucius but not much is known about him as no records about him survive. He is traditionally regarded as the founder of Daoism and the author of the Daodejing - a collection of 81 chapters that holds the concealed answers to existence, to what is and what isn't. The core of the book is the Dao, or the Way. In essence it is “nonaction” (wuwei) - “Do nothing and everything is done.” It implies spontaneity, noninterference, letting things take their natural course. Everything that is comes from the unlimited and effortless Way, which existed before heaven and earth.

Lao Zi is venerated a saint or god in popular religion and was worshipped as an imperial ancestor during the Tang dynasty (618–907). According to some modern scholars, Laozi is entirely legendary.

The Western Zhou Dynasty was established in 1100 BC. Although the system left over from the Shang Dynasty was still in use, people began to resist the old etiquette and ideas. During this period, people began to collapse morally, there were wars between feudal lords, and the political and social instability was extremely unsettling. Two historical figures emerged at the right time. One was Lao Zi. The other was Confucius (557-479 BC).

Confucius has had more influence on Chinese thought and culture than any other figure in China’s 5,000 year history. For the Chinese, his life teachings provide examples of the highest good attainable by man making him a larger than life figure. He was a social reformer and mentor, hoping to restore calm to turbulent times. Chief among his philosophical ideas is the importance of a virtuous life, filial piety (virtue of respect for one's parents) and ancestor worship. He emphasised the necessity for compassionate and prudent rulers, that rulers and teachers are important role models for wider society, the importance of inner moral harmony and its direct connection with harmony in the physical world(8).

Prominent medical literature

With the development of writing, many books were recorded in the Zhou Dynasty. Medicinal substances were recorded in Rites of Zhou, The Book of Songs and The Classic of Mountain Seas(2). The Book of Songs is a collection of poems from the Zhou Dynasty (the Spring and Autumn period) and is considered the beginning of Chinese poetry. The origin and efficacy of 300 kinds of medical plants, minerals and animal substances were described in the Book of Songs with poetic note(1). Some of the herbs described are still widely used today – date/da zao (Fructus Jujubae), Goji berry/gou qi zi (Fructus Lycii), peach kernel/tao ren (Semen Persicae), mugwort leaf/ai ye (Folium Artemisiae Argui) , mulberry leaf/sang ye (Folium Mori), angelica root/bai zhi (Radix Angelicae Dahuricae), kudzu root/ge gen (Radix Puerariae Lobatae), skullcap root/huang qin (Radix Scutellariae), peony/shao yao (Radix Paeoniae Alba seu Rubra), Chinese dosser seeds/tu si zi ( Semen Cuscutae), etc.(2).

The Classic of Mountains and Seas is a geographic book on Chinese mountains and rivers, in which 52 medicinal plants, 3 minerals and 67 animal medical substances are found. The medical substances were classified into tonics, revival agents, disease preventatives, contraception, aids for growing seeds, pest destroyers, medication for livestock diseases, poisons, and antidotes to poisons. It is from the Western Zhou dynasty onward that people began to obtain knowledge of poisons(2).

The Book of Rites, also known as Li Ji is one of the Five Classics of the Confucian canon. It describes the social forms, governmental system, and ceremonial rites of the Zhou Dynasty. In regards to medicine the Book of Rites warns people to “only seek the services of doctors that have medical experience handed down from their great grandparents”. It placed importance on the inherited knowledge and experience of the doctor which will become a traditional prerequisite in China for a doctor to be held in high regard even today(2)

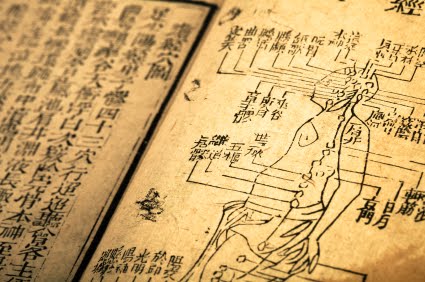

The foundation of Chinese life sciences and Chinese medicine is the legendary book "Huang Di Nei Jing" (黄帝内经) or "The Yellow Emperor's Inner Classic". It is the earliest and most important written work of traditional Chinese medicine. It combines the views of different schools and depicts natural law defining health and disease through the concept of "Yin and Yang" and the "Five Elements" doctrines.

Although it is said that the Nei Jing was written by the emperor, it is actually a collection of several authors who have assembled their work over a long period of time. It is a synthesis of two books, Su Wen (Basic questions) and Ling Shu (Numinous spindle) but after the Han dynasty, each part began to circulate separately. The Su Wen was completed in the Spring and Autumn Period and modified in the Warring States Period. It is written in a question-and-answer format between the Yellow Emperor and various physicians from ancient times. It outlines the understanding of Chinese medicine regarding illness, medicines, diagnosis, and treatment, and since has provided guidance to Chinese doctors in their practice of medicine. The Huangdi neijing has been the highest Chinese authority on medical matters for over 2,000 years.

YS

(1) "History of TCM" in-class presentations by medical students at Shenzhen University, China, 2016

(2) Tu Ya / Fang Tingyu (2014). History and Philosophy of Chinese Medicine. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House

(3) Unschuld, Paul (1943). Medicine in China. London: University of California Press, Ltd.

(4) Ho, Peng Yoke / Lisowski, Peter (1997). A Brief History of Chinese Medicine and its Influence: Second Edition. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing.

(5) Sato, Masayuki (2003). The Confucian Quest for Order: The Origin and Formation of the Political Thought of Xun Zi. Leiden: Brill.

(6) Yao, Xinzhong (2003). The Encyclopedia of Confucianism: 2-volume set. Abingdon: Routledge

(7) Wu, Chung (2008). The Wisdom of Zhuang Zi on Daoism. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.